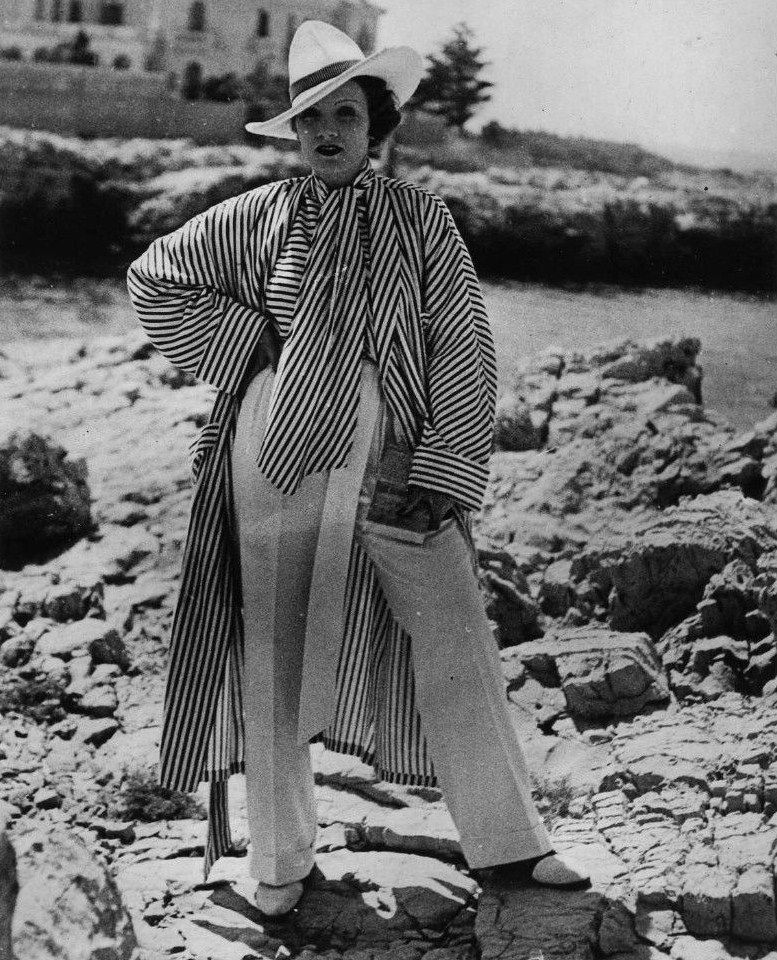

Through their performances, the members of the Sewing Circle changed what it meant to be desired. To be an ‘object.’ They paved the way for new and enduring beauty standards that accepted androgyny as a way to appeal to both men and women. By the end of the 1930s, half of the highest paid actresses were involved in sapphic romances, and this was visualized in their signature looks.

They didn’t make themselves available to the male subject—their vulnerability was only recognizable to the other women who had felt it. Stereotypical images, like all aspects of culture, change and evolve over the years. Queer women in classical Hollywood films often appeared as spinster aunts or prison matrons, but by the 1970s, they were often being represented as vampires, a trope that turned same-sex love and affection into something cruel and monstrous. By the twenty-first century, a wide variety of openly queer people and queer “looks” has made it more difficult for the mass media to create new stereotypes, but traces of the old ones can still be discerned. Many of these stereotypes originated in the Golden Age, despite what the Hays Code would have you believe. The Sewing Circle created a distinctly female gaze both with their performances and costume design, almost like a secret language for film loving sapphics. Their secret is safe with me.

Bibliography:

Madsen, A. (2015). The Sewing Circle: Hollywood’s greatest secret– female stars who loved other women. Open Road Media.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Film Theory and Criticism : Introductory Readings. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford UP, 1999: 833-44.

Modelski, Tania. “Introduction.” Essay. In The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory, 1–14. Methuen, 1988.

Modelski, T. (1988). Femininity by Design. In The Women Who Knew Too Much: Hitchcock and Feminist Theory 89–101. Methuen, 1988.

Queen Christina. United States: Loew’s Inc., 1933.

Pommer, Erich, Carl Zuckmayer, Vollmöller Karl, Robert Liebmann, Rittau Günther, Hans Schneeberger, Friedrich Hollaender, et al. The Blue Angel, 1930.

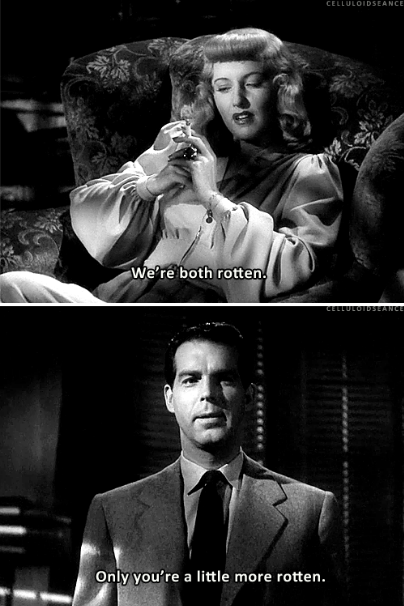

Double Indemnity. United States: Paramount, 1944.